Guard Duty: An Analysis of Half-Life: Blue Shift

By gamer_152 4 Comments

Note: This article contains major spoilers for Half-Life and Half-Life: Blue Shift.

Last week, I unpacked Half-Life: Opposing Force, and I didn't make my disappointment with it much of a secret. Valve's Half-Life delicately integrated you into its setting, but Opposing Force's Black Mesa kept you at arm's length and, in the late game, rallied Shock Troopers and Voltigores to snipe you the second they saw you. The expansion was devoid of a narrative goal for its protagonist and crammed fifteen pounds of weapons into a ten-pound bag. It's, therefore, a joy to say that Gearbox's second Half-Life expansion, Blue Shift, welcomes you back into the facility like a prodigal son and exhibits a remarkable restraint in assigning your loadout.

Commissary

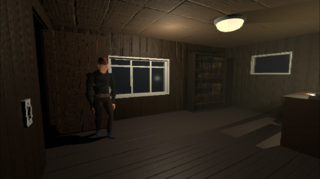

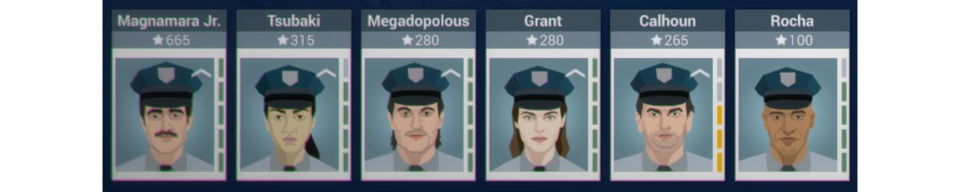

The narrative and game design of Blue Shift flow from who you play. As security guard Barney Calhoun, you are once again an associate of the other Black Mesa personnel, but right from the opening scene, the story makes it clear how a change of job can be a change of social status. The first level, Living Quarters Outbound, is a near neighbour to Half-Life 1's Black Mesa Inbound. If an audience has already experienced a scenario once, they become sensitive to the differences between a close recreation of it and the original. This allows a creator to highlight subtle outliers that distinguish the two scenes. Barney, like Gordon, begins his day with a tram ride from the dormitories to his department, but where the transit for researchers appears diligently maintained, the track for the guards protests its use with violent sparks. When Barney reaches the guards' prep and rest area, Freeman speeds past en route to the anti-mass spectrometer while one of Calhoun's coworkers struggles to open the front door.

As Gordon, socialising with other physicists always felt stilted and formal, but there's more camaraderie among the guards. You visit their barracks in Level Two, Insecurity. There's a communal area to lounge around and eat snacks, and the boys chat about those beers they owe each other. But the security in this club is subordinate to the scientists, and they aren't afraid to let you know. One egghead threatens to get a guard fired if they can't allow them access to their office, and when you head down to the elevators at the end of Insecurity, a researcher comes out with this:

"Well, it's about time. We don't pay you people to mosey around at your own convenience. Make this thing work".

If it's not already apparent that the guards get Black Mesa's grunt work and table scraps, you'll discover it through your objectives and item locker. The original Half-Life furnished you with fourteen weapons, with Opposing Force upping your claim to sixteen. Blue Shift is positively minimalist, limiting you to just nine instruments of aggression. A glut of guns may have choked this shooter's first expansion, but sometimes, it feels like its sequel is overcorrecting. Every firearm you slide into your holsters appeared in the two previous Half-Life instalments, and most of them in the early days of their campaigns.

You've had more than enough time to get acquainted with the Glock and the M4, yet they loiter, and without any new cohorts by their side. All the same, I can't deny that the weapons you do get are balanced enough to feel timeless, and you're pushed to stretch each as far as you can. Your division is on a budget, and you don't have the obliterative luxury of a soldier's arsenal like Shepard or the products of clandestine experiments like Freeman. You are security and must make do.

Out of Scope

A more cynical reviewer might tell you that Blue Shift cannot mechanically nail down the guard aesthetic. Barney is mending transmitters and priming batteries, but shouldn't his remit be standing between civilians and Headcrabs, pistol in hand? Not necessarily. Plenty of hirelings at the bottom of company ladders are forced to stray outside their job description and perform a range of menial tasks. You see it happen all the time with teachers and janitors. In Black Mesa, we have a group of men who are paid to protect, but as the stage Insecurity shows us, they're also expected to run the I.T. systems and fix the elevators.

The further a workplace falls into dilapidation, the more consuming this job creep becomes. As employees leave and demand for production and maintenance increases, there's more work to be done by fewer people, and that labour isn't going to be carried out by the senior employees. The higher your rank, the more sway you have in the company, and the organisation can't risk driving out the workers they value more dearly. So, the extra tasks fall upon the backs of the more easily replaceable parts, who may already be designated the "odd jobs" and who might have more practice at them anyway. In Half-Life, the resonance cascade fractures a research facility, and it's up to Barney to flood the coolant tanks and close the steam valves to get the scientists out. After all, the guards are already the resident bug fixers, and who else is going to do it? The scientists? The only one of them who would be capable is Gordon Freeman, and he's got higher priorities.

But with personal safety at an all-time low and the intellectuals desperate for someone who will put their life on the line, this is Barney's chance to become a hero. He is permitted an arc that no other character in this series is. He rockets from a lackey whom his superiors are at ease reprimanding to someone who gets to operate tech alongside the researchers, and eventually, to a knight in shining armour. In the final level, Deliverance, a scientist tells Calhoun they owe him their lives.

Home Sweet Home

In this side story, we play a borderline custodial worker, so some corners of this Blue Mesa feel a bit banal. I say that as someone with a ravenous appetite for industrial art. You can be standing knee-deep in the filthy water plant of Duty Calls and start asking yourself, "This is an empowerment fantasy?". On the other hand, this expansion sees Half-Life's environmental realisation rise from the grave, and we bask in its glory.

The stage Captive Freight is a train yard where we must search cargo wagons to find scientists, and comes complete with a section of track where we turn a carriage on a table. Power Struggle has us charging a battery and engaging in charging-a-battery-related activities. In Focal Point, the trip to Xen, our hands are wrenched off the wheel of the scientific institution, but so they should when we're travelling outside its fortress walls. In the teleportation lab (Focal Point, A Leap of Faith), we set up the transporter. Lastly, while Duty Calls' canal and water processing station are quotidian, we do get to turn valve and bust turbines to unclog the plant.

Duty Calls

It's during the transition from Insecurity to Duty Calls that the resonance cascade does its cascading. Watching disaster from the window of an elevator may not sound like fun, but you still get all the chaos of a building's stitching snapping. Flaming metal falls from the roof, and the cart plummets. When you land, you find the impact was more than the scientists' bodies could take. Red lights flash, an alarm blares, and a creepy robotic voice heralds the end for Black Mesa. As the security guard, it's us who turns off the alarm. With that din silenced, we're left in the eerie quiet, knowing they will soon arrive. A couple of theatrical phrases in Duty Calls tell us how depraved our adversaries are. Marines dump a body down a pipe, casually complaining as if they'd been asked to take out the trash, and a couple of Headcrab Zombies try to rip a guy right down the middle.

It's not all sunshine and dislocated shoulders. Duty Calls is where you'll find the sluggish and irritating cargo puzzle. To reach the ladder at the top of its room, you must adjust two platforms to the right heights and move a barrel and a crate nearby, cobbling together some ersatz stairs. But the pulley for the platforms inches along at a sub-glacial speed and unless you ram the boxes at an angle perfectly perpendicular to them, you'll slide off them like rain on glass. The effect is amplified with the barrels as they're rounder than the crates with a smaller surface area.

The camera is also not fit for purpose. A player's view should orient their character within the larger context of entities that they can affect and that could affect them in the near future. Else, the player should be able to change their perspective to get that view quickly. When the player starts pushing a huge palette of goods, they take control of an object larger than the default avatar, one that affects a wider area. Therefore, the camera should fit more of the world into view.

Plenty of other games have us enter a "crate mode" when we start jostling objects bigger than the player character, and in these modes, the camera trucks backwards to fit more into the viewport. When you ask Blue Shift for that courtesy, it stands there and shrugs its shoulders. Left with only a first-person perspective, it's difficult to tell if we've positioned a crate or barrel appropriately relative to the platforms around it, at least while still pushing it. At ground level, these items partially obscure our sightlines, and when trying to jump onto one, there's always the chance you'll accidentally nudge it because the lip of it disappears below the camera. We also can't pull objects, meaning that if we've shoved one too far forward, we need to run around the other side and line ourselves up again to correct our mistake.

These flies remain in the ointment across all box interactions in these games. Chapter Six, Power Struggle, has a more rotten version of this puzzle where you must line up a rank of barrels and then run to a distant room to fill the barrel exhibit with coolant. These containers are light enough to float on the surface of the liquid, and you're trying to make a bridge out of them to get to the far side of the area. If you don't get your barrel alignments or air control right and fall into the coolant, it's insta-death. Even if you catch your mistake before you leap, you have to return to the coolant panel room to drain the fluid, return to the barrel room to adjust the canisters, go back to the panel room to fill the tank again, and then return one more time to barrel purgatory. It's enough to make you want to blow up the containers. You're in luck because that is also something you can do in Duty Calls.

The exploding crate puzzle is simple when you break it down. There's a turbine you need to destroy to continue, as well as a freight elevator with a combustible box on it. You lower the crate and push the box into the canal. When it hits the turbines, it rips their fins from their shank, clearing the river. This sequence doesn't sound like it should be pride of show, but it's resplendent with slick design touches that make it land.

When you reach the waterway, a never-ending stream of crates is caught in the tide. That current carries the boxes into the fans that then crush them. So, you have a clear indication of what direction the water moves in, that it can carry crates with it, that crates stay buoyant in it, and that if you try to squeeze through the fins, they will rip you apart. There is a sign that cautions you not to push explosives into the turbine, which lets you know sending boxes into the mechanism is an option and is a devilish bit of reverse psychology. Of course the player will want to disobey the rules and wreak havoc. When our dynamite does show up, the designers also have Vortigaunts ride down on the lift with it. This keeps the section from becoming too inert and shows that action and puzzle sequences do not have to be mutually exclusive.

Captive Freight

As we enter Chapter Four, Captive Freight, we come across the USMC's calling card: a broken keypad. The stage's military theming permits us access to the big guns: Satchel Charges, the M4, Grenades, and Explosive Barrels. Immediately, it's not the Soldiers that we contend with. Instead, the Black Mesa warehouses have the same problem many others do: vermin, which comes in the form of harmless roaches and baneful Headcrabs. When we later test our mettle against the military, there are choke points in which we emerge from skinny doorways into vast container parks, a tip of the cap to Opposing Force. We get our revenge on the army when we unbox a thoughtful present: the Minigun. This mounted weapon lets us vapourise a platoon as they charge through a yawning gate. There's also a minor reference to the military trapping Freeman in the original game when some problem customers lock you in a train carriage.

Those are the positives. The negatives of Captive Freight are scatterbrained signposting and AI pathing. The objective of the level is to find and secure Doctor Rosenberg, who has the know-how to evacuate people from the facility safely. Like other escort NPCs, Rosenberg can bump into corners and freeze, but more problematically, he sometimes spontaneously vanishes. I've run down a corridor, turned around, and found that the good doctor is missing. Can you tell this guy works with teleporters? All you can do in these instances is backtrack through what should be cleared stage on a manhunt.

The best prevention is deliberately slowing your progress through the level so you're never putting too much distance between Rosenberg and yourself. If you can't find him, you're also unlikely to uncover the mounted gun. Its housing looks like many of the impenetrable crates strewn about the trainyards. While trying to determine which train cars contain scientists or how to redeem your Minigun, you're also listening to an abrasive loop of physicists banging on metal and crying for help. Guh.

Focal Point

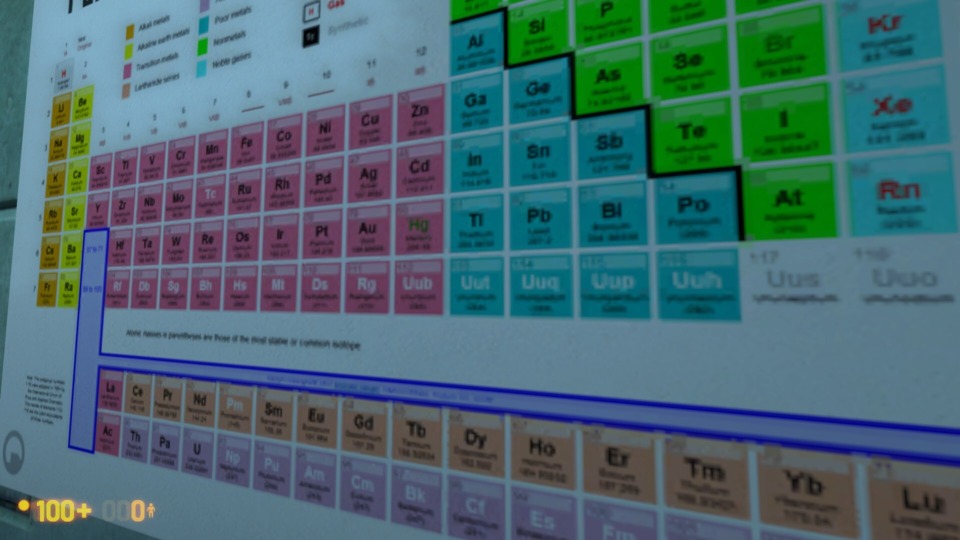

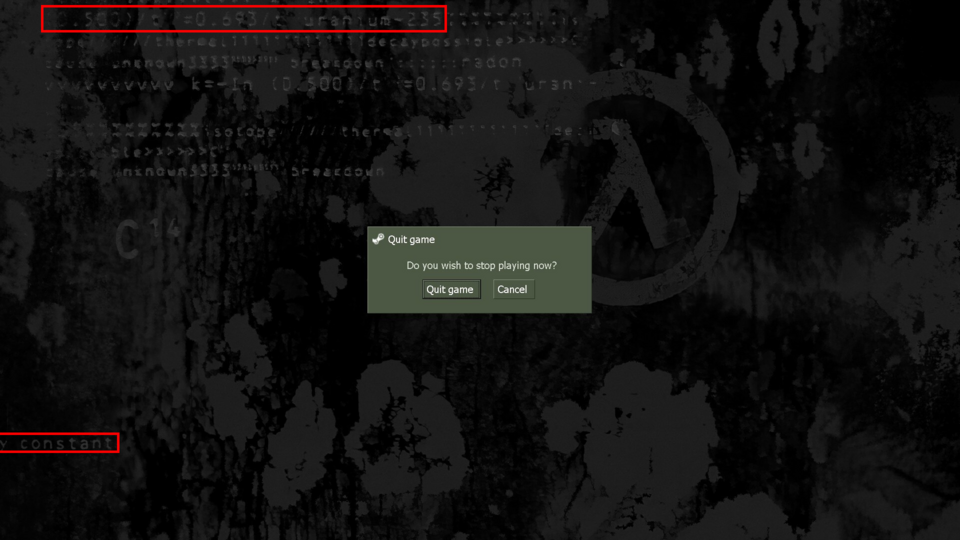

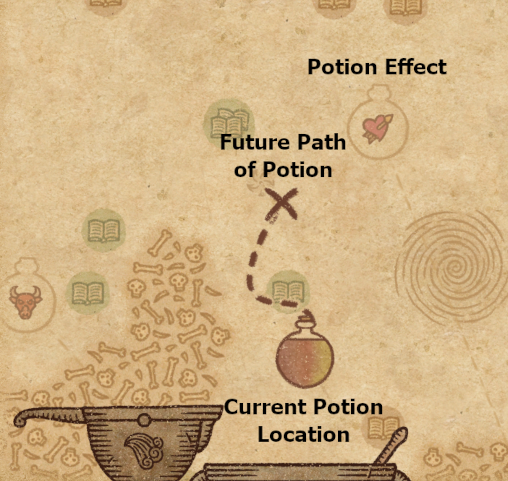

Focal Point takes us back to Rosenberg et al.'s lab, where their teleporter can place us on the road into the New Mexico desert, but only if it's properly persuaded. Black Mesa's teleportation technology uses a fascinating, hacky workaround to slingshot travellers from A to B. Unable to send people directly to a destination, the researchers have to use Xen as a connecting station before pulling the teleported people back down to their terminus. This could be how the invasion from Xen happened: Black Mesa's teleporter technology laid the rails to that dimension, and something travelled back down them. Like Crowbar Collective's Xen, Gearbox's shows signs of a vanguard from the research facility arriving there before the aliens visited Earth.

During Barney's layover in the outworld, he will retune the Black Mesa teleporters there, with Blue Shift as a whole taking the form of the proxy teleportation Rosenberg describes. In the base Half-Life, Xen was the end of the line. In Blue Shift, the border world is somewhere we return from, our vacation to it falling in the middle of the campaign. After Captive Freight, a hub crowded with human enemies, a stage that's entirely extraterrestrials is warranted.

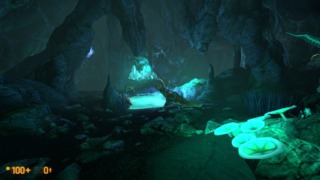

Some of the passages in Focal Point's alien geology house underground lakes. They remind me of the creepy cave diver videos you can find on YouTube. The metallic echoes in these crawlspaces make them sound too much like vents when they're supposedly rock or biological formations. However, Focal Point does serve as a riposte to Valve's Xen, showing it's possible to have an alien world with platforming challenges but without moving scaffolds or janky ambulation.

Power Struggle

Blue Shift's sixth chapter is Power Struggle. In one of my playthroughs, all of my saves for Power Struggle corrupted. I used console commands to jump ahead to Chapter Seven, but for whatever reason, the mechanised door at the start of that stage wouldn't open. Thank god I kept an old save from an earlier run, or that could have been my campaign over then and there. With a litany of games today activating in a glitchy state, you often hear players lamenting how games "used to release finished". They're right that there was a period when entertainment software was more stable, but you can't look back too far. Blue Shift was born during a long era of video game history when it was normal for products to fall apart in your hands. Count me thankful that the technology progressed.

I do like the routing in this basement. You have an exit elevator, a coolant basin, a room which you fill the basin from, a room where you see a little play in which a Vortigaunt kills a couple of employees, a room where you charge the battery, and a room where you activate the power. It's not always clear where to go next, but the game manages to link all those ventricles together so that each chamber is only a stone's throw from every other. It does that while allowing an alternative return route through the stage after you've filled the power cell. I also love what the level does with the power gauge. The player needs to know whether electricity is flowing in the department because until it does, they can't complete their goal of charging the battery. The power meter in this level is an early example of diegetic UI, and it indicates whether the circuit is online.

So, where should the designers place the indicator showing the circuit is on? Do they glue it next to the level's entrance or about halfway through? Both would be opportune waypoints at which to remind the player of their objective. But then perhaps the UI element belongs in the breaker room, so after players throw the switch, they can see they've gotten the place humming again. What Gearbox realises is that they don't have to park the indicator in any one place. They embed a power meter in each of those locations I mentioned, making your success status a frequent fixture in the diegetic UI.

Leap of Faith, Deliverance

A Leap of Fatih and Deliverance are the seventh and eighth chapters. While Half-Life and Opposing Force end with a boss fight, Blue Shift sings itself off with a high-pressure thriller sequence. You and Rosenberg prime the teleporter to get you the hell out of dodge. In the previous two Half-Lifes, teleportation was a battering ram with which to invade. In Blue Shift, it can be a lifeboat. The plan doesn't go off without a hitch. At the last moment, you appear to be stuck in a stochastic nightmare, teleporting to random locations without any control, but then the bug resolves itself. As a general rule, protagonists shouldn't have their problems solved for them; the audience finds it more meaningful when characters put in effort to make their dreams a reality. Flouting that rule, Barney Calhoun gets a freebie, and the script traps him in this spatial flux just to release him without contest.

Barney only rescues three whitecoats. It's hardly the grand heroics we saw from Gordon, but a life is a life, and I respect that Blue Shift believes four people are enough to be worth caring about. Given the 100-decibel, cringey humour of Borderlands, restraint is probably the last trait you'd associate with Gearbox Software. However, the studio shows praiseworthy self-discipline over the course of this expansion, including during its ending.

A Different Wavelength

In a multitude of senses, developing content for another studio's game is less strenuous than building a title from scratch. You start with a platform, assets, gameplay systems, and a world. But in other senses, it is more challenging. You're handling unfamiliar tools, putting on an impression of someone else, and constrained to the possibilities of the engine you've been given. Blue Shift is one of the driest shooters I've ever played, and that means that even in 2000, some people were going to find it too much of a wallflower. From the vantage point of 2024, the physics and technical stability of Blue Shift are also outdated. Some of that will be down to the greenness of Gearbox at the time and the industry of that generation knowing less about the theory of entertaining players. Some of it will be down to what the GoldSrc engine was missing.

Yet, nothing can take away from Gearbox that this is the expansion where they imitated Valve with shocking legitimacy. This game exudes the original Half-Life's ethos of putting you in touch with scientific and industrial organisations by letting you touch one. We're all aware of the power of environmental storytelling, but we often reduce the technique to set dressing. Half-Life and Blue Shift make the case that if video games are an interactive medium, then an environment is best conveyed through call and response. Thanks for reading.

Log in to comment